Invision and AP/Evan Agostini

Ted Lechterman, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and his wife, MacKenzie Bezos, recently announced a plan to spend US$2 billion of their $164 billion fortune on homeless shelters and preschools.

Since Jeff Bezos has taken flack for giving away far less of his money than some other billionaires, such as Bill Gates, the announcement may look like a sign that this tech titan is becoming more generous. The announcement also responds to criticism of the $1 billion per year that Bezos already spends on Blue Origin, his space travel experiment.

But as a political theorist who studies the ethics of philanthropy, I think Bezos’s charitable turn raises grave concerns about the pervasive power of business moguls.

Disturbing trend

The Bezos family’s philanthropy is following an unsettling pattern in terms of its timing. Amazon’s market value had recently topped $1 trillion, raising more questions than ever around Amazon’s overwhelming size and power.

This wasn’t the first time that Bezos effectively redirected attention from Amazon’s immense clout with a big announcement about philanthropy. When news broke in 2017 that Amazon was acquiring Whole Foods, raising new concerns about the company’s retail domination, Bezos made a dramatic public appeal through Twitter for advice on how to focus his giving.

The timing may have been coincidental both times, but the suspicion that philanthropy distracts the public from questionable conduct or economic injustice is a familiar worry. Since the days of robber barons like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, social critics have charged that philanthropy is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

This cynical view holds that magnificent acts of generosity are nothing more than cunning attempts to consolidate power. Like dictators who use “bread and circuses” to pacify the masses, the super-rich give away chunks of their fortunes to shield themselves from public scrutiny and defuse calls for eliminating tax breaks or raising taxes on the wealthiest Americans.

AP Photo/Cliff Owen

Good intentions are not enough

Today, political theorists who study philanthropy – like Emma Saunders-Hastings and Rob Reich – tend to think the problem is more complicated. They accept that many philanthropists are sincere in their desire to help others, and the solutions donors develop are sometimes remarkably innovative.

But they also contend that noble intentions and strategic thinking aren’t enough to make philanthropy legitimate. And my own research reaches a similar verdict.

That’s because massive donations can perpetuate inequality and threaten democracy in several ways.

Dramatic acts of charity by the ultra-wealthy may reduce pressure on governments to tackle poverty and inequality comprehensively. Depending on private benefactors for access to basic necessities can reinforce social hierarchies. And when the elite spend their own money on essential public services like housing the homeless and education for low-income children, it lets the rich mold social policy to their own preferences or even whims.

In other words, even if Bezos has great ideas, no one elected him or hired him to house the homeless and educate kids before they enter kindergarten. Great wealth is not a qualification for all jobs.

Tax privilege

The tax deductibility of the donations made by the richest Americans can exacerbate these concerns because it effectively subsidizes their giving. Some scholars argue that the point of tax incentives is to encourage donations for things the government can’t or shouldn’t support directly – like maintaining a church property.

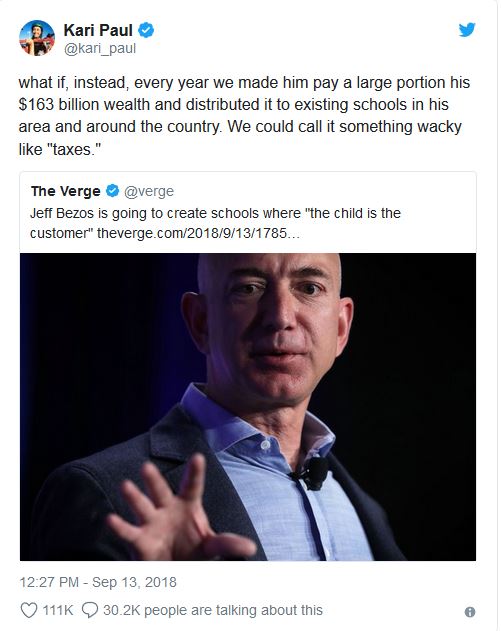

Observers, including MarketWatch reporter Kari Paul and Guardian columnist Marina Hyde, have noted that if people like Bezos and the businesses they lead were to stop fighting for low tax rates, democratically elected officials would have more money to spend tackling big problems like homelessness and other urgent priorities.

By making tax-deductible donations, they argue, Bezos is effectively diverting tax dollars to fuel his private judgments about public policy.

Questions about accountability and generosity

My research indicates that using tax deductions to supply essential public services, such as education and housing assistance, may be a misuse of this privilege because it has the potential to undermine democratic control.

Members of the public have a vital interest in being able to oversee the provision of goods and services that support their most basic needs. This kind of accountability is possible only when these needs are served by democratic governments, not rich benefactors operating in their place.

And Bezos’s behavior as a businessman has raised other questions about his generosity and respect for democracy. When Amazon’s hometown of Seattle proposed to tackle runaway housing costs with a tax on the city’s largest employers, Amazon resisted. The city backed off after the company threatened to scale down its Seattle operations if the bill passed.

It may seem odd that someone who opposed a tax intended to help cover housing costs for his low-income neighbors would want to spend part of his fortune on housing. But to me it makes sense, because in my view, Jeff Bezos’s beef isn’t with his duties to help the least fortunate, but with the limits on economic power that democracy requires.![]()

Ted Lechterman, Postdoctoral Fellow, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.